LEW ARCHER, A MODERN HERO:

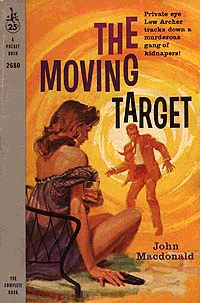

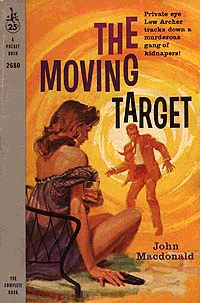

* 1949: The Moving Target

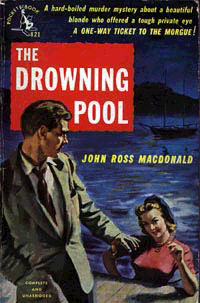

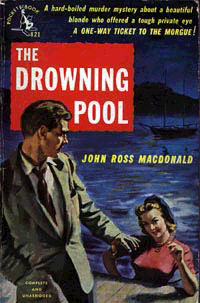

* 1950: The Drowning Pool

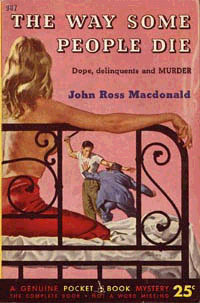

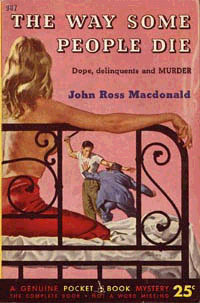

* 1951: The Way Some People Die

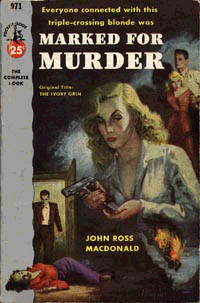

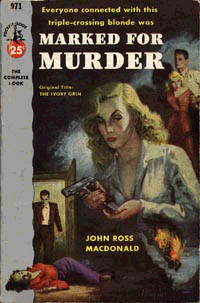

* 1952: The Ivory Grin

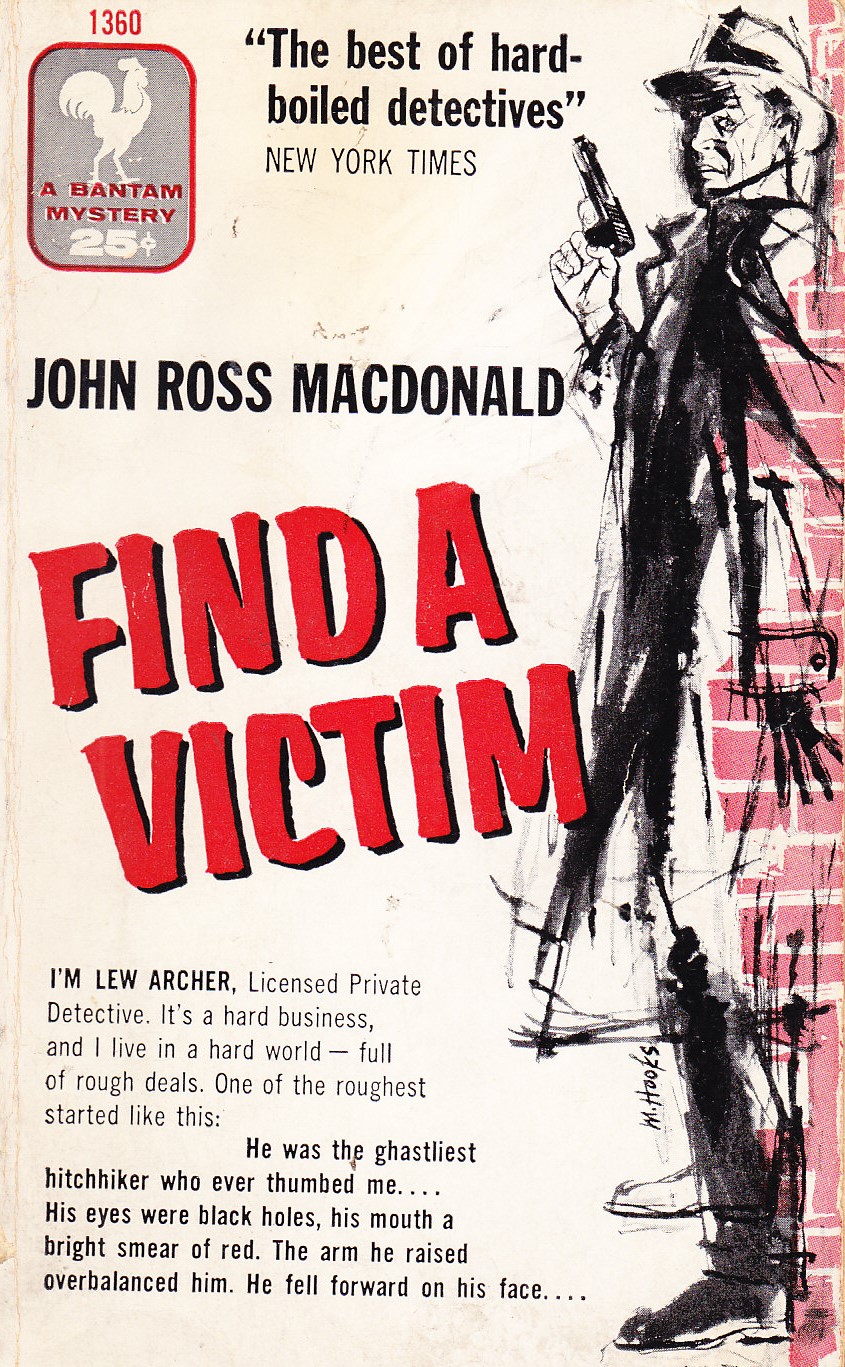

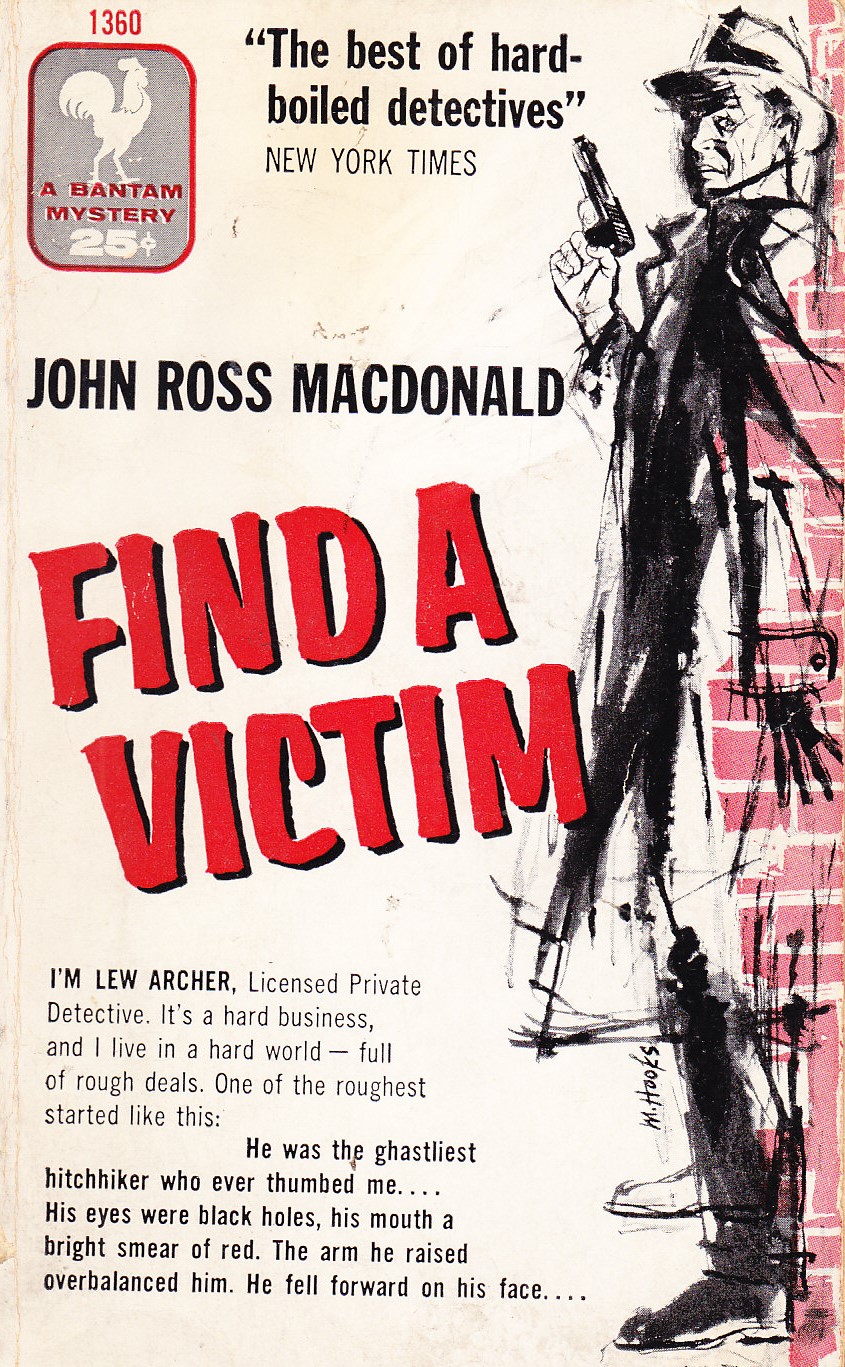

* 1954: Find A Victim

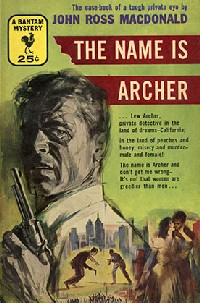

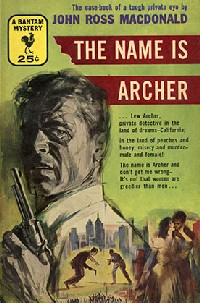

* 1955: The Name Is Archer

* 1956: The Barbarous Coast

* 1958: The Doomsters

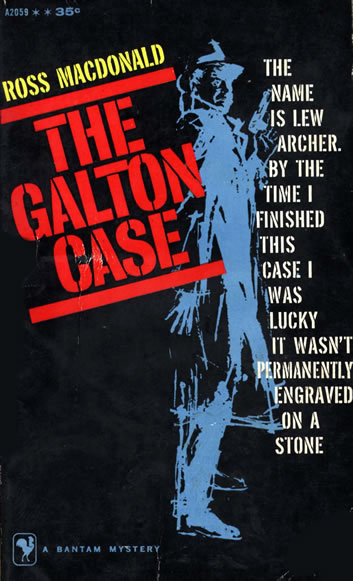

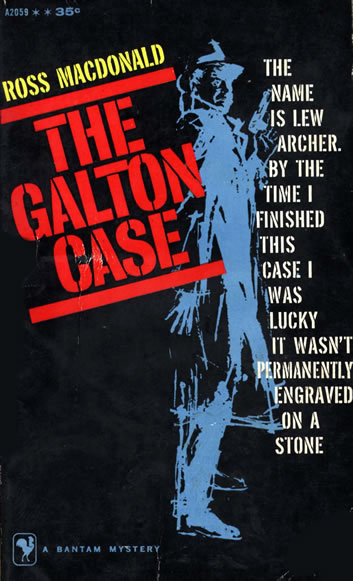

* 1959: The Galton Case

* 1961: The Wycherly Woman

* 1962: The Zebra Striped Hearse

* 1964: The Chill

* 1965: The Far Side of the Dollar

* 1966: Black Money

* 1968: The Instant Enemy

* 1969: The Goodbye Look

* 1971: The Underground Man

* 1973: Sleeping Beauty

* 1976: The Blue Hammer

"AN UGLY WOMAN

WITH A GUN IS

A TERRIBLE THING"

The switchboard operator was a frozen virgin who dreamed about men at night and hated them in the daytime.

The switchboard operator was a frozen virgin who dreamed about men at night and hated them in the daytime.

A death mark like a little red birth mark, and Taggert was thirty dollars' worth of organic chemicals shaped like a man.

I watched her over my salmon mayonnaise; a tall girl whose movements had a certain awkward charm, the kind who developed slowly and was worth waiting for. Puberty around fifteen, first marriage or affair at twenty-one. A few hard years outgrowing romance and changing from girl to woman; then the complete fine woman at twenty-eight or thirty.

In the close air, the smell of spilled rancid grease from the stove and the sick-sweet odor of dime-store perfume from the dresser were carrying on an old feud. I wasn't rooting for either. "Cosy," I said.

When I pulled the heavy door open, the noise blasted my ears. Most of it came from the platform at the rear end of the room, where a group of young men in white flannels were maltreating a piano, a guitar, a trombone, a trumpet, drums. The piano tinkled and boomed, the trombone brayed, the trumpet squawked and screeched. The guitar bit chunks from the chromatic scale and spat them out in rapid fire without chewing them. The drummer hit everything he had, drums, traps, cymbals, stamped on the floor, beat the rungs of his chair, banged the chrome rod that supported the microphone. The Furious Five, it said on his biggest drum.

Parking spaces in downtown Hollywood were as scarce as the cardinal virtues.

A colored boy was working on a punching-bag fastened to the corner of the wall. On the other side of the alley a negro woman was watching him across a board fence.... He was light-heavy, I guessed, but he didn't look more than eighteen, in spite of the G.I. pants. With his height and heavy bone-structure, he'd grow up into a heavy-weight. The woman looked as if she could hardly wait.... After a while he'd be a fighting machine hired out for twenty or twenty-five dollars to take it and dish it out. If he was really good, he might be airborne for ten years, sleeping with yellower flesh than Violet, eating thick steaks for breakfast, dishing it out. Then drop back onto a ghetto street-corner with the brains scrambled in his skull.

The pianist could have passed for a corpse in any mortuary if he had only stayed still, instead of tossing his fingers in bunches at the suffering keyboard. His batting average in hitting the notes was about .333, which would have been good enough for a Coast League ball-player. He was white and loaded to the gills, it was hard to tell with what. I sat down at a table near the piano and watched him until he turned his face in my direction. He had the sad bad centerless eyes I expected, wormholes in a withered apple with a dark rotten core. I ordered a beer from a sulky waitress in an orange apron. When I left her the change from a dollar, she hoisted a long-suffering smile from the depths of her despair and offered it to me: "Zizi's as high as a kite. They ought to make him shut up when he's so wild, instead of encouraging him.

I drove into the court and parked in front of the office. It was a dismal cubicle, divided by an unpainted wooden counter. A frayed canvas settee stood by the door. On the other side of the counter there was a rolltop desk stuffed with papers, an unmade studio bed, an electric coffeemaker full of grounds, over all a sour coffee smell. A dirty printed card scotch-taped to the top of the counter announced: We Reserve the Right to Choose Our Clientele.

The fat man came back to the office, his belly rising and falling under the T-shirt. His forearms were marked with blue tattooings like the printing on sides of beef. One on the right arm said: I Love You Ethel. His small eyes said: I love nobody.

His living room was the kind of room you find in back-country ranch-houses where old men hold the last frontier against women and civilisation and hygiene. The carpets and furniture were glazed with dirt. Months of wood ashes clogged the fireplace and sifted onto the floor. The double-barreled shotgun over the mantel was the only clean and cared-for object in the room.

His fingers moved across the unfamiliar contours of his face. "I kind of wish you didn't knock off Faustino. I was counting on doing it myself."

"You won't be circulating. Any exterminating you do will be bedbugs in a jail cell."

The Dewdrop Inn was a rundown stucco ell with sagging shutters and doors that needed paint. Its office door was opened by a woman who was holding a soiled bathrobe tight around her waist. She had frizzled red hair. Her skin had been seared by blowtorch suns, except where her careless breast gleamed white in the V of her robe. She caught and returned my dipping glance, letting the V and the door both open wider.

"I'm looking for a woman."

"What a lucky coincidence. I'm looking for a man."

Miss Parish had emotional equipment to match her splendid physical equipment. The thunderclouds came into her eyes again, with lightning.

"He's not responsible!" she cried. "Can't you see that? You mustn't judge him."

"You like Carl," I said in a neutral tone.

The young woman colored, and answered rather sharply: "You would, too, if you knew him when he's himself."

Maybe I would, I thought, but not the way Miss Parish did.

Carl Hallman was a handsome boy, and a handsome boy in trouble was a double threat to women, a triple threat if he needed mothering. Not needing it, and none being offered, I left.

The man who came in next radiated chill from green glacial eyes. He had a cruel nose and under it the kind of mouth that smiles by stretching horizontally. He must have been nearly sixty but he had a well-sustained tan and a lean quick body. He wore a light fedora and a topcoat.

The man who came in next radiated chill from green glacial eyes. He had a cruel nose and under it the kind of mouth that smiles by stretching horizontally. He must have been nearly sixty but he had a well-sustained tan and a lean quick body. He wore a light fedora and a topcoat.

So did the man who moved a step behind him and towered half a foot over him. This one had the flat impervious eyes, the battered face and pathological nervelessness of an old-fashioned western torpedo. When his boss paused in front of me, he stood to one side in canine watchfulness. Tommy moved up beside him, like an apprentice.

"You' re quite a mess." Schwartz' s voice was chilly, too, and very soft, expecting to be listened to. "I' m Otto Schwartz, in case you don' t know. I got no time to waste on two-bit private eyes. I got other things on my mind."

"What kind of things have you got on it? Murder?"

He tightened up. Instead of hitting me, he took off his hat and threw it at Tommy. His head was completely bald. He put his hands in his coat pockets and leaned back on his heels and looked down the curve of his nose at me:

"I was giving you the benefit, that you got in over your head without knowing. What' s going to happen, you go on like this, talk about murder, crazy stuff like that?" He wagged his head solemnly from side to side. "Lake Tahoe is very deep. You could take a long dive, no Aqualung, concrete on your legs."

"You could sit in a hot seat, no cushion, electrodes on the bald head."

The big man took a step toward me, watching Schwartz with a doggy eye, and lunched around with his big shoulders. Schwartz surprised me by laughing, rather tinnily:

"You are a brave young man. I like you. I wish you no harm. What do you suggest? A little money, and that' s that?"

"A little murder, Murder everybody. Then you can be the bigshot of the world."

"I am a bigshot, don't ever doubt it." His mouth pursed suddenly and curiously, like a wrinkled old wound: "I take insults from nobody! And nobody steals from me."

Dis Culligan steal from you? Is that why you ordered him killed?"

Schwartz looked down at me some more. His eyes had dark centers. I thought of the depths of Tahoe, and poor drowned Archer with concrete on his legs. I was in a susceptible mood, and fighting it. Tommy Lemberg spoke up:

"Can I say something, Mr Schwartz? I didn't knock the guy of. The cops got it wrong. He must of fell down on the knife and stabbed himself."

"Yah! Moron!" Schwartz turned his contained fury on Tommy: "Go tell that to the cops. Just leave me out of it, please."

"They wouldn't believe me," he said in a misunderstood whine. "They' d pin it on me, just because I tried to defend myself. I was the one got shot. He pulled a gun on me."

"Shut up! Shut up!" Schwartz spread one hand on top of his head and pulled at imaginary hait. "Why is there no intelligence left in the world? All morons!"

"The intelligent ones wouldn't touch your rackets with a ten-foot pole."

"I heard enough out of you."

He jerked his head at the big man, who started to take of his coat:

"Want me to work him over, Mr Schwarz?"

It was the light and meaningless voice that had argued with Culotti. It lifted me out of my chair. Because Schwartz was handy, I hit him in the stomach. He jackknifed, and went down gasping. It doesn't take much to make me happy, and that gave me a happy feeling which lasted through the first three or four minutes of the beating.

Then the big man's face began to appear in red snatches.

She opened the door wide and turned on all the lights and urged me in. She was a thirtyish blonde in an imitation mink coat which had seen better days. So had she. One of those blondes who ripened early like California fruit, hung in full teen-age maturity for a few sweet months or years, then fall into the first high reaching hand. The memory of the sweet days stayed in them and fermented.

Closing the door she brushed against my back in a movement which was either erotic or alcoholic. The odor of gin which she wore instead of perfume suggested the latter possibility. But she opened up her minkless mink and gave me a dazzling smile across her figure. Touch me if you dare, the smile said: I dare you, but don't you dare. They never got over their grudging need of the reaching hands that violated their first fine careless narcissism.

I got out my wallet and produced a card which a Santa Monica life insurance salesman had presented to me before he found out what I did for a living.

I was beginning to get some idea of Fablon. In these circles he was a fairly common type: the man who tried everything and succeeded at nothing.

The orchestra was playing again, and through the archway I could see people dancing in the adjoining room. Most of the tunes, and most of the dancers, had been new in the twenties and thirties. Together they gave the impression of a party that had been going on too long, till the music and the dancers were worn thin as the husks of insects after spiders had eaten them.

She shifted the position of her body, as if its substantiality and symmetry might divert my attention from the jerry-built flimsiness of her story.

Bess came out of the room. She had changed into a dress which had to be hooked up the back and I was elected to hook it up. Though she had a strokeable back, my hands were careful not to wander. The easy ones were nearly always trouble: frigid or nympho, schizy or commercial or alcoholic, sometimes all five at once. Their nicely wrapped gifts of themselves often turned out to be homemade bombs, or fudge with arsenic in it.

The cashier of Mercy Hotel had eyes like calculators. She peered at me through the bars of her cage as if she was estimating my income, subtracting my expenses, and coming up with a balance in the red.

"How much am I worth?" I said cheerfully.

"Dead or alive?"

That stopped me.

The people at the slot machines inside seemed to work by similar mechanisms. They fed in their quarters and dollars with the left hands and pulled the levers with their right like assembly-line workers in a money factory. There were smudge-eyed boys so young that they hadn't begun to shave yet, and women with workmen's gloves on their lever hands, some of them so old and weary that they leaned on the machines to stay upright. The money factory was a hard place to work.

He didn't offer me his hand, which was just as well. I don't like shaking hands with men wearing rings with stones in them.

She was pretty enough to make me concious that I hadn't shaved.

Our gazes, mine as impassive as hers I hoped, met, struck no spark, and disengaged. The female spider who eats her mate held no attraction for me. She rose decisively but gracefully, as though she had practiced the movement in front of a mirror. An expert bitch, I thought as I followed her high slim shoulders and tight-sheathed hips down the stairs to the bright street. I felt sorry for the army of men who had warmed themselves, or been burned, at that secret electricity.

In the final glare of day I could see the old closet dust in the groove of his hat, and the new sweat staining the hatband.

I followed him down a narrow aisle between two lines of wrecked cars. With their crumpled grilles and hoods, shattered windshields, torn fenders, collapsed roofs, disemboweled seats, and blown-out tires, they made me think of some ultimate freeway desaster. Somebody with an eye for detail should make a study of automobile graveyards, I thought, the way they study the ruins and potsherds of vanished civilisations. It could provide a clue as to why our civilisation is vanishing.

RELATED LINKS

- FACEBOOK/GROUPS

- SLEUTHSAYERS.ORG

- KALIBER38.DE

- LITERARINESS.ORG

- AMAZON

- KILLERCOVEROFTHEWEEK.BLOGSPOT.COM

- BEARALLEY.BLOGSPOT.COM

- THRILLINGDETECTIVE.COM

...

The man who came in next radiated chill from green glacial eyes. He had a cruel nose and under it the kind of mouth that smiles by stretching horizontally. He must have been nearly sixty but he had a well-sustained tan and a lean quick body. He wore a light fedora and a topcoat.

The man who came in next radiated chill from green glacial eyes. He had a cruel nose and under it the kind of mouth that smiles by stretching horizontally. He must have been nearly sixty but he had a well-sustained tan and a lean quick body. He wore a light fedora and a topcoat. The switchboard operator was a frozen virgin who dreamed about men at night and hated them in the daytime.

The switchboard operator was a frozen virgin who dreamed about men at night and hated them in the daytime.